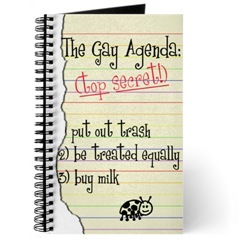

Image Ganked with Gratitude from EverydayCitizen.Com

You don’t have to be a California citizen to know that, on top of the presidential election that has most of the nation (and a large portion of the globe) holding its breath, Tuesday has huge stakes for Californians specifically. As an absentee voter, I’ve already seen the ballot, and as a social policy geek, I found myself defensive when I saw that particular art/ science so misused in the various propositions presented to California voters. (I address California’s in particular because that’s the ballot I shared this time around, but I hardly expect it’s much better anywhere else.) Prop 8, which is hardly the only ill-informed measure seeking approval (and which Melissa Etheridge’s son has officially proclaimed lame), seeks to ban same-sex marriage, legally defining marriage as between a man and a woman. You probably already know that. And you may remember that, despite California’s largely progressive reputation, same-sex marriage has actually only been legal in California since mid-May, when the state’s Supreme Court declared that sexual orientation was not “a legitimate basis upon which to deny or withhold legal rights.” Although where I’m currently stationed in America’s “heartland,” California is perceived as something like that radical black-sheep uncle, who — when family functions come around — is conveniently left off the invitation list, the chances that Prop 8 will pass remain strong, stronger actually than my stomach does considering them. California did elect the Gubernator, remember, and although I’m the same girl often in trouble among her engaged friends for stubbornly insisting she has no desire to marry, I am waiting for Wednesday with an uncomfortable amount of nerves.

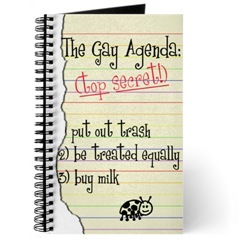

I want to talk a little bit about this so-called piece of legislation, not to persuade anyone to vote against it (if I know you, you read this, and you have a vote in CA, you’re already opposing it, to my knowledge), and not because I think people are unaware of this issue, but because the way the debate is being framed speaks to an issue I see surfacing again and again in the queer community — the gay and lesbian community specifically — that really frustrates me, even though I feel I understand the impulse guiding it. On a surface-level, it has to do with confusion and conflict between essentialist and social constructionist perspectives, but more basically, it remains a simple fundamental fact of fear.

Let me offer a simplified lesson in perspectives for anyone new to these terms. (I promise you’ll have encountered the ideas behind them, even if the words for those ideas are new.) An essentialist perspective basically states that people are born with certain personality characteristics, which are hard-wired into their biology and their genetic make-up. So, if an essentialist is looking at gender, she or he is likely to tell you that boys are born more aggressive, more rowdy, and more active than girls, who are born more nurturing, more polite, and more passive. A hard-core social constructionist would completely disagree with that notion, saying that at birth we are basically blank slates, and we learn gender (or whatever characteristic we’re discussing) through social rules, imitation, reinforcement, reward systems, et cetera. The social constructionist would say that most girls prefer to play with dolls because they’re encouraged to do so, while most boys dislike playing with dolls because they experience a negative response from others when they do. Although a lot of people believe in a middle ground between the two ideas (not entirely negating the role of biology or the fact that it does, in fact, interact with environment), there remains a sense that certain aspects of self are simply hard-wired, and that this hard-wiring somehow makes them more legitimate. I think of it as similar to physical versus mental illness. In the States, a physical illness is considered “real” in a way that mental illnesses rarely are, at least by the general population. Character traits are often the same: in order to be legitimate, they must be proven biological.

The same goes for sexuality. As a pretty strong social-constructionist, I don’t believe that I was born gay, a fact which often shocks people I’m talking to, partly because it puts me in a minority (within a minority) and partly because the majority of society has only considered two options regarding “alternative” sexualities: Either we were born this way or we chose it. To suggest that sexuality is a choice, when the reality of it — given the times — can result in anything from divorce to death, is entirely unfair. I don’t believe that, even slightly. But I also don’t believe that I was gay as an infant, that I have a gay gene, that straight people don’t have a gay gene, or that they were born straight. (What about bisexual people? Do they have a less-active gay gene? How does this work? No, wait. Don’t answer that.) What I find interesting is that, when we’re inclined to legitimize or de-legitimize certain sexual orientations, we embrace a weirdly conflictual combination of essentialist and social constructionist perspectives. For instance:

The multi-million dollar “Yes on 8” campaign has aired a series of ads, one of which suggests that if the proposition fails, California children will be taught about homosexuality in the classroom, from a very young age, which will undermine heterosexuality and marriage as institutions, and — basically — ensure the impending Apocolypse. Never mind that there is nothing about education in the proposition, never mind that no sex ed starts as young as we’re supposedly planning to target these kids, and never mind that you can’t teach someone a sexual orientation. One would think the failure of so-called reparative therapy would have proven that by now, but apparently it hasn’t. The scare tactic they’re employing is the same one employed by opponents to gay parents adopting: if we have access to children, we will replicate our “pathology.” We will somehow “teach” or “convince” kids to be gay. (Because it’s so much fun. Ok, actually it is. But not so much during election season.) What’s interesting about this is that almost none of the people who believe this believe they learned, were convinced, or chose to be straight. Since hetero is the “natural” / default sexuality, the homophobic population for the most part presumes that it’s an essential trait, the way they were born, and the right way to be born. (Unquestionable essentialism, right?) But in the same breath, they can turn around and say that a minority sexuality was constructed by a certain kind of environment, that we must protect “our kids” against these kinds of environments, and that homos must have their sexualities re-constructed through appropriate therapies.

The only way this makes sense, to whatever extent it does, is to acknowledge that the majority of these lgbtq opponents believe that homosexuality is some sort of pathology, which could develop in a fundamentally different way than a “healthy” heterosexuality develops. So, that’s their excuse for the hypocrisy, which I can shake my head at it and dismiss. But… speaking from the queer minority, what’s ours?

Because, let’s be clear here, we do it, too. We may be more consistent, but as a population we’re not supporting a social constructionist viewpoint. In fact, we’re terrified to do so because we recognize how dangerous it is for us. The idea that I wasn’t born gay leaves me vulnerable to a slew of arguments. “Well, what happened?” (I don’t know. What happened to make you straight?) “Then how is it natural?” (Who said biology was the only legitimate science?) “You mean you chose it?” (No more than you chose to be het’ro.) “Isn’t that an argument for reparative therapy? I mean, if you were turned gay, couldn’t you be turned straight?” (I never said I was “turned” gay… for all I know, we’re born neutral, or perhaps with predispositions in favor of something that can shift in time. The fact that it wasn’t hard-wired at birth doesn’t mean it isn’t hard-wired now, and I could no more easily turn myself straight than a straight person could turn themselves gay, which most of the homophobes are willing to admit is a toss-up between “not bloody likely” and “frikkin impossible.”) All of these arguments are arguments I use; they are — to an extent — my arguments, ones I’ve adopted and shaped and written as conversations have replayed (with different people) again and again over the years. But they’re flawed arguments as well, and from my perspective, the overall argument of the queer community that we were born queer is equally flawed. Bill Richardson crashed and burned in the HRC/ LOGO forum with the Democratic presidential candidates because he suggested people weren’t born gay. He wasn’t trying to be radical; he fumbled an easy question and later claimed jet lag — but the fact that it was intended to be an easy question is telling. The formation of sexuality is not uncomplicated; it’s not something we understand entirely, but the queer community, having been put on the defensive, has simplified it tremendously. We’ve gone in search of a gay gene, we’ve carved in stone a narrative about having known from childhood that we were different somehow, we’ve decided our queerness is biological to protect its validity, and in doing so, we’ve entirely ignored the real argument we need to be making.

It doesn’t matter why… because it isn’t wrong.

Seriously. It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter if I’m gay because of my genes, or my brain chemistry, or the state that I live in, or the way I was raised, or the friends that I have, or the air that I breathe, or the books that I read, or the time I was born, so on and so forth beyond infinity. It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter how I got to be the way I am (interesting as it can be to speculate and study possibilities) because who I am does not need validation. My sexuality doesn’t need a biological basis in order to be approved. An environmental basis doesn’t make it any less real, any less fundamental, or any less an active facet of who I am. My sexuality is not a pathology. Not mine, and not anyone else’s.

Look at those earlier questions again. What if the answer to “What happened?” was “I don’t know, but I’m happy it did!” What if the answer to “How is it natural?” was “because it feels like a fit”? What if, when people asked me if I chose this, I could safely admit to them that if I had received a “select your orientation” form growing up, (which I can assure you I did not), I would have chosen the sexuality I have. Because I like it, it fits for me, it works. It’s right for me.

As for reparative therapy, we’re making the wrong argument there, too. We’re arguing, constantly, that sexuality can’t be changed and that it’s psychologically damaging to try. The part about psychological damage is true; the part arguing against sexual fluidity is more problematic for some people. But we could just as easily be arguing that it doesn’t matter whether these “therapies” work or how well. There’s no pathology for them to cure. Why treat something that isn’t wrong? It’s a waste of energy. You might as well treat me for preferring cookie dough ice cream to mint chocolate chip. Your ability to re-wire my preferences is irrelevant. It’s the goal itself that’s wrong.

On Tuesday, Californians are voting on Prop 8, and hopefully they’re voting in favor of an individual’s right to love in the way they see fit. But in the meantime, we’ll continue hearing all these bullshit arguments about the biological basis for marriage. Having to shake my head at them for that is one thing. But having to shake my head at us for playing the same essentialist game, without having questioned the rules? I’ll proclaim that one lame myself.